Veitnamese and Chinese New Year celebrations remind us of the many Asian Americans we have in the U.S.

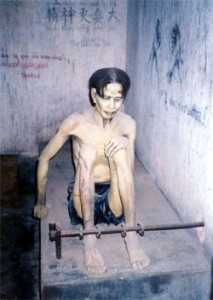

The Vietnamese Americans are the fourth largest Asian group in the US (Chinese, Asian Indian, and Filipino are the top three). Their mass migration started after 1975 at the end of the Vietnamese War. At that time, people were fleeing Vietnam as refugees and came to the US with little material resources, although a strong ethic and desire for education and for their family to succeed. They left their homeland under duress. If they had stayed, they or their loved ones (father, mother, brother, sister) would have become a political prisoner, perhaps tortured and killed. They had little choice. Once here, however, they have embraced the US as their new homeland, with the intent to stay. They have assimilated politically, economically, even culturally.

from: http://images.chron.com/photos/2008/06/25/11826402/600xPopupGallery.jpg

from: http://www.inminds.co.uk/vietnam-tiger-cage.jpg

http://beirut.indymedia.org/ar/2006/03/3861.shtml.

At the same time, remembering their roots and valuing their own ethnic traditions are an important underpinning of their communities and families. While the first generation is not as wealthy on average as the first generation economically motivated Chinese immigrants (remember, most refugees come with little to no resources—no matter what their social and economic status was at home), they have poured their commitment into their children and their children’s success. Today, many second generation Vietnamese have completed college, become professionals, and can be considered successful in the US society.

From: http://assets.makers.com/maker/Connie%20Chung%20Portrait.jpg.

http://www.makers.com/moments/chinese-americans

The Chinese Americans are the largest, and certainly among the oldest Asian ethnic groups we have. [Note: I am using Asian as the US Census does: people with origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent.] San Francisco’s Chinatown, which was established in the 1840s, is the oldest Chinatown in the US and has the highest density of Chinese-American residents. Most of these are, or were originally, from Guangdong province and Hong Kong and, therefore, are Cantonese speakers—Remember when I greeted you last week with Gong Hei Fat Choi! for Happy New Year? The reason is because historically most of our Chinese immigrants came from these southern areas; areas that have a long tradition of migrating out of their country for jobs and other economic opportunities. (Note: this includes other Chinese languages, but I’m using Cantonese as a catch-all for the Yue language branch of Chinese.) In the past, mostly men came and stayed in their new host country in order to make a living and send money home. Some of these men returned to their home areas periodically to take a wife, who may have remained in his home village living with his parents, or (once our immigration laws changed) brought them to the US to live.

In the last 10 to 20 years or so, more and more of our Chinese immigrants from mainland China are Mandarin speakers. This is bringing a change within the Chinese-American communities in terms of language use. Mandarin apparently is taking over as the lingua franca of the American Chinese diaspora. However, I must say that when I overhear a group of Chinese at a University or in a large, mixed group setting speaking with each other, they use English. Perhaps English is considered a “neutral” third language for them—one which doesn’t privilege any one of the various Chinese languages over another. Not to mention the fact that it is also the common language of the US and they all are adept at its use.

In terms of modern immigration, more and more mainland Chinese are emigrating to the US through the EB-5 Investment Visa, which allows powerful, wealthy Chinese access to US citizenship. Under the EB-5 Visa, established in 1990 (under the first President Bush), a green card is given with the right to permanent US residency in certain US states. This type of Visa is given to those who invest at least US$500,000 in projects listed by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Servies (USCIS) (http://www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/permanent-workers/employment-based-immigration-fifth-preference-eb-5/eb-5-immigrant-investor).

Population Change among Chinese Americans:

Year population increase over

According to Census past 10 years

1980 806,040 + 85.5 %

1990 1,645,472 + 104 %

2000 2,432,585 + 47.8 %

2010 3,347,229 + 37.6 %

Naturally, the Chinese and Vietnamese Americans will be found at all levels of the U.S. socio-economic ladder but, overall, both of these immigrant groups have contributed quite a bit to our country. Personally, I am happy with the diversity they’ve added to our cultural understanding, yes, but (I’m being VERY selfish here) they’ve each (as with other Asian cultures) brought wonderful variety to our food cuisine! I love American comfort foods, but who can resist the flavors and textures of these “new” dishes?! If you’re interested in learning more, go on the Internet and type in foods from whatever country intrigues you—you will have a bountiful harvest!

Enjoy!

Final Note:

To check on how many people are in each ethnic group in the US go to: http://www.census.gov/. You can get 2013 data as well—in some areas.

A site where delicious recipes are generously shared is: http://rasamalaysia.com/.

A good paper on Vietnamese in the US today is at: http://www.bpsos.org/mainsite/images/DelawareValley/community_profile/us.census.2010.the%20vietnamese%20population_july%202.2011.pdf.

For a quick overview of Chinese in the US see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_American#Statistics_of_the_Chinese_population_in_the_United_States_.281840.E2.80.93present.29.