It may surprise people that, as noted in the previous post, the Chinese invention of gunpowder (or really protogunpowder) is attributed to a monk. However, as with many inventions, there is an element of serendipity at play here. Monks, Taoist priests, and alchemists in general used the ingredients which make up gunpowder for other purposes, in particular, as medicines and elixirs of immortality. They were not looking for explosives; they were looking for ways of prolonging life. However, when these specialists mixed certain ingredients together, they sometimes got an entirely different result then intended!

The author of a 9th century text warned Taoists looking for an immortality elixir to be careful when mixing sulphur, arsenic sulphide, and saltpetre because it could badly burn them and even burn down their buildings! Needham (p 31) says this is the first reference to protogunpowder.

It does not take a big jump in thinking to move from accidental explosions to controlled explosions. And it makes sense that it would be among the monks, Taoist priests, and alchemists who would do this and not someone from the military.

Originally, these explosions weren’t harmful, just exciting and noisy. They were used to scare off ghosts and evil spirits and in celebrations. However, as so often happens with inventions, the relatively harmless rocket that had explosive materials in it was soon turned into a bomb as well.

From the 11th and into the 13th century Chinese bombs were like rockets—in that they weren’t really very destructive because the proportion of nitrate was low. As I mentioned above, Needham refers to these early forms as protogunpowder bombs. At most they would explode with a “whoosh,” much like the rockets they were based on—frightening, but not very destructive. However, as the percent of nitrate was increased the bombs became serious weapons which were able to blow up walls and city gates.

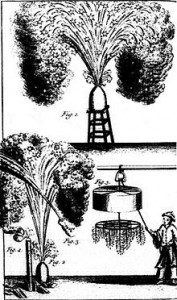

By the Ming Dynasty in the 14th century, such fragmentation bombs (as that shown at the top of this post) were filled with iron pellets and pieces of broken porcelain. This bomb was used in war and was designed to mutilate enemy soldiers (from Huo-long-jing, a Ming Dynasty text, part 1, chapter 2 from en.wikipedia.org).

What a long journey for these materials–to go from a hopeful immortality elixir to a source of mutilation and destruction!

References: Joseph Needham: Science in Traditional China & Clerks and Craftsmen in China and the West; Wikipedia

[pinterest]